The Island (Ostrov)

By John O'Brien, S.J.

2006, Director: Pavel Lungin. 112 min.

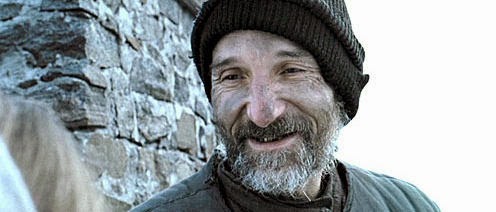

Actors: Pyotr Mamonov, Viktor Sukhorukov, Dmitriy Dyuzhev

Music: Vladimir Martynov

Plot

During World War Two, a worker on a Russian coal barge, Anatoly (Mamonov), is given the choice by Nazi boarders to either shoot his captain, Tikhon, and have the chance to live, or be shot alongside him. Anatoly chooses the first option, and then falls overboard as the Germans scuttle the boat. Three decades later (in 1976), Anatoly is living an ascetic life at a monastery on an island. He lives in a boiler house, and spends his time wheeling coal from the wrecked boat to feed the furnaces that warm the monastic houses. He walks the island saying The Jesus Prayer (“Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me a sinner”) and asking Tikhon to pray for his soul. The monks tolerate his presence, despite his habit of pulling “pranks”, unpredictable acts that unnerve them. Anatoly, it is clear, is something of a “holy fool”, and also appears to have gifts, such as the ability to heal, predict the future, and exorcise demons; diverse people come to the island seeking him out. Some of the monks, such as Father Job (Dyuzhev), struggle with envy, and resentment at Anatoly’s antics, while the superior, Father Filaret (Sukhorukov), though bewildered, is inspired to try to overcome his own inordinate attachments.

During World War Two, a worker on a Russian coal barge, Anatoly (Mamonov), is given the choice by Nazi boarders to either shoot his captain, Tikhon, and have the chance to live, or be shot alongside him. Anatoly chooses the first option, and then falls overboard as the Germans scuttle the boat. Three decades later (in 1976), Anatoly is living an ascetic life at a monastery on an island. He lives in a boiler house, and spends his time wheeling coal from the wrecked boat to feed the furnaces that warm the monastic houses. He walks the island saying The Jesus Prayer (“Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me a sinner”) and asking Tikhon to pray for his soul. The monks tolerate his presence, despite his habit of pulling “pranks”, unpredictable acts that unnerve them. Anatoly, it is clear, is something of a “holy fool”, and also appears to have gifts, such as the ability to heal, predict the future, and exorcise demons; diverse people come to the island seeking him out. Some of the monks, such as Father Job (Dyuzhev), struggle with envy, and resentment at Anatoly’s antics, while the superior, Father Filaret (Sukhorukov), though bewildered, is inspired to try to overcome his own inordinate attachments.Film History

Winner: Best Film, Best Actor, Best Director, Best Sound, Best Supporting Actor, Best Cinematographer at the Nika Awards (the "Russian Oscars") in 2007. Also nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival, 2007. Closed the Venice Film Festival in 2007.

The Island can justifiably be compared to any work by Tarkovsky or Bergman.

Spiritual Reflection

The Island is a strange movie with a surprising capacity to arrest us in spiritual ways. It lingers on in the imagination long after the closing credits. This is usually a sign that a film has inner depths that may not be available to us entirely at the conscious level, but has nonetheless managed to speak to our spirit. Russian filmmakers are particularly good at this.

What is the point of this story of a guilt-laden Orthodox brother who apparently “wastes” his life atoning and mourning an ancient mistake? The sorrow and penance seems disproportionate to the crime. Surely he has confessed his “sin”, committed under extreme wartime pressure, and found redemption, especially at a holy place like the monastery? To our modern sensibility, Anatoly seems obsessed in an unhealthy way with his sin. Get over it! God is merciful! You have confessed your sin: go, and sin no more!

But The Island does not offer this scenario. Instead, we have a man who has embraced a life of atonement, “whose sin”, as the psalm says, “is always before him.” He does not wish to simply let it go. He does not reject God’s mercy, but nor does he presume he has received it. Rather, he continuously begs for it, both for himself and for others. He is, indeed, a strange sort of Christian. We get the sense that he has a role to play in the world, perhaps bearing an odd vocation, an unusual prophetic mission, but it’s hard to get a handle on it. He reminds us of the more outlandish of the Old Testament prophets, like locust and honey-eating John the Baptist, a wild-man clothed in camel-skin, who by his very strangeness and urgency, has a message that rings as loud and pure as a clarion call.

Moreover, he might remind us of Ezekiel, whose mission of calling Israel to return to God went unheeded, forcing him to make ever more exagerated signs. The Lord asks Ezekiel to lie on his side in full view of the people for more than a year. During that time he has a dietary prescription: “And you, take wheat and barley, beans and lentils, millet and spelt, and put them into a single vessel, and make bread of them” (Ez 4:9). So far, not so bad. Whole grains are healthy, aren’t they? But wait, the Lord continues: “And you shall eat it as a barley cake, baking it in their sight on human dung.” Human dung. For over a year, Ezekiel must cook his food on burning human feces. Perhaps Ezekiel was crazy for agreeing to be God’s prophet. But God was so exasperated by his people, we infer, that he was desperate to get their attention (although, we should note, God relents somewhat about the human feces bit, and allows Ezekiel to burn cow dung).

To understand Anatoly in The Island, we might see his calling in the same prophetic vein, like certain saints such as Francis of Assisi, whose countrymen also thought him out of his mind. And, in a certain sense, Francis was. He embraced contagious lepers, talked to animals, danced and sang like a madman. Yet he also performs miraculous deeds, founds the largest religious order ever seen, reforms the papacy, nearly reconverts the world of Islam, and reboots the Christian world. Francis was God-intoxicated, saturated with God, and had a powerful effect on nearly all of western civilization.

Anatoly's life, by contrast, is more hidden. And there may be another dimension to his life than just "holy tomfoolery". He carries his guilt through it all, as if he has glimpsed, in a profound way, his own sinfulness as an objective fact, grasped how much he and he alone owns his sinfulness, and perhaps has even seen his place among the eternally lost. He may have realized – in the final analysis – that he does not then “deserve” anything, has no inherent “right” to anything, other than his sin. In fact, his sense of sin, extreme as it may seem, could actually be part of his spiritual mission. As we see, his gifts of clairvoyance and healing, which are linked to his humility, bring about great good in the lives of others.

The film director, Pavel Lungin, has said he doesn't regard Anatoly as being clever or spiritual, but blessed “in the sense that he is an exposed nerve, which connects to the pains of this world. His absolute power is a reaction to the pain of those people who come to it.”

Yet, “typically, when the miracle happens, the lay people asking for a miracle are always dissatisfied” because “the world does not tolerate domestic miracles.” They want a magical result, while God is just asking for simple faith, which is confounding. Dmitry Sobolev, the screenwriter, explains: “When a person asks for something from God, he is often wrong because God has a better understanding of what a person wants at that moment.” God wants us to ask for things, but he also wants us to trust him. We have to be ready to accept the answer.

This casts light on the unusual role that Anatoly’s poor and apparently wasted life may have played in the grander scheme. His brand of sanctity may consist in allowing the pain of his guilt to meet the pain of others in a direct and salvific way. Since his guilt is imbued with faith in God’s saving power and goodness, it is elevated beyond the level of meaninglessness and neurosis, and becomes a power based on a deep awareness of his own smallness. He sees what very few see clearly: that we are truly children. The consequence of this awareness of spiritual childhood is nothing short of revolutionary: the awakening of the spiritual senses, and the possible transformation of the world.

It is not likely that many are called to be one of the yurodivy, or “holy fools” that are part of the Russian spiritual tradition. Nor should we confuse their “prophetic insanity” with real mental illness. But their example, when they occasionally flash across the horizon of normal human community, points to something important: They show us Christ. They teach us much about living a right-ordered life, and model for us the way of radical trust, of humility, and of forgiveness. Thus they are islands of sanity and healing in the sea of the world.

Be sure to read the speech of actor Pyotr Mamonov at the premiere of The Island.

Prayer Questions

1) Was there something about the spiritual attitude of Anatoly that challenges me, whether positively or negatively. Ask myself why this is so, and ask God the same question.

2) Pick one or two spoken lines from the film that you remember and meditate on them. Chew them over, taste them, and extract their deeper meaning. Try to do this without “over-analyzing”. Let the words themselves speak to you as you consider them.

3) Pick one or two visual images from the film that stand out most vividly, and meditate on them, in the same way as (no. 2). Gaze on the image and let the image gaze on you. Let your meditations turn, finally, into prayer.

Comments

Post a Comment