Walking to Loreto

The idea of making a pilgrimage, that is, journeying to a place of spiritual significance, is commonly understood by Catholics and non-Catholics alike, but as to what may be entailed by an Ignatian pilgrimage might require some explanation.

Basically, such a pilgrimage is undertaken after the example of that perennial pilgrim St. Ignatius of Loyola, who wanted to follow the steps of the first disciples of Christ, who were sent to preach without any provisions (Mt 10:5-16, etc.), and to rely entirely on whatever God would provide. It was in this spirit of trusting in Providence, that I, too, set out for an eight-day foot pilgrimage in Italy, with one travelling companion, no money, just a razor and a toothbrush between us.

We were both, it should be said, living in Rome and discerning our vocations. A pilgrimage such as this was both indicative of our youth and anticipatory of the consecrated life to which we were drawn.

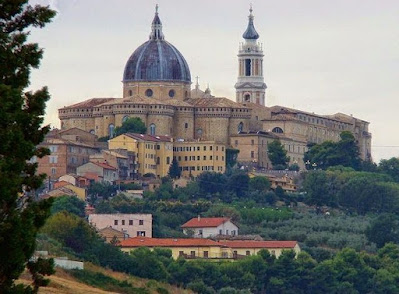

Our destination, we decided, would be the Marian shrine at Loreto near Ancona, close to the Adriatic coast in the region of Le Marche. It had been visited over the course of 700 years by a long list of saints, including Ignatius.

But why Loreto? And who is Our Lady of Loreto? Why that title and why that place? A thousand years ago, the knights known as the crusaders had taken the holy land from the Muslims (who had conquered it from the Byzantines) and made Nazareth their capital. An Italian family named the Angeli had decided to restore the house in Nazareth known to have been Mary's. When a Muslim army won a key victory near Nazareth, the Angelis took down the stones of the house and shipped them to Italy where they were reassembled in its present location of Loreto. Later a basilica was built around the stone house, and still later the little house was enclosed in marble. It became one of the most visited Marian shrines in Europe.

To begin our pilgrimage, my companion and I took the train to a town called Jesi, which I had calculated was about a 7-day walk from Loreto. We found the local cathedral, and commended our endeavour to the Lord. Our prayer was primarily that we might seek the Kingdom in manifold ways, rather than simply to find food and somewhere to sleep. We tried to be conscious of this in the days that followed.

After wandering the streets of Jesi we met a husband and wife who oversaw a kitchen for the disadvantaged (including in this case, your pilgrims). After supper the same Christian couple took us to a hostel and paid for our lodging there. This proved to be a kind of leitmotiv during the pilgrimage, namely a sense of vulnerability and poverty that was responded to in unexpected ways.

The life of the pilgrim is not only one of simple joys, such as encountering the generosity of others or the free feeling of the ‘open road’, but also a certain humility or rather humiliation of having to beg for food and to accept when that request is granted or denied. After the consolation of Jesi, the next night we experienced the desolation of having nowhere to stay. We just continued walking into pitch darkness of the countryside, and eventually attempted to sleep on a grassy bank beside the road. We were probably still a little shy to be begging randomly. The sleep was fitful and full of insects.

In the following days, we experienced both rejection, from a parish priest who probably thought we were scamps (and maybe we were. I appropriately shook the dust from my sandals before leaving) – and also the hospitality of another parish priest, an elderly parroco who gave us beds to sleep on and invited us to his table for dinner. It was the feast of St. Peter and Paul, and he said that under no circumstances could he refuse two strangers, who might as well have been Peter and Paul. He had been the parish priest in that town for 50 years.

At the end of the fourth day, we found accommodation in the town of Osimo, which turned out to be the place of the tomb of St. Joseph of Cupertino, the ‘flying friar’ of levitation fame. The next day, while walking along the narrow streets of the town, we spotted an open door, with sounds of joyful activity coming from within. It was a parish centre hosting a party for a group of immigrant children, and amazingly, we two pilgrims (also technically immigrants) were admitted to the feasting and games.

The next day we played basketball in a park with a few Italian youth. Our only witness to the Gospel was when we announced that we were off to daily Mass, causing some astonishment.

On the afternoon of the fifth day, I found myself quite hungry, and as we were walking down a country road, we came across a fig tree, laden with dark ripe figs. Thankful, I ate a few. We carried on, but before long, with the hot Italian sun beating down, I became sick to my stomach, and started vomiting beside the road. It was, I must say, a low point, and I couldn’t muster the will to go any farther. We spotted a monastery in the valley below. I groaned to my companion, perhaps a bit melodramatically, to go on ahead without me, and ask for sanctuary. Some time later, he returned and said the Franciscans there were willing to help us, but the superior wanted to talk to us first. We were brought to his office and interrogated at length. He couldn’t wrap his mind around the idea of two anglophones tramping the roads of Italy on pilgrimage. Most people flew to Loreto or drove in coach buses. Besides, who were we exactly? Not exactly seminarians, but foreigners deciding on religious life? I found his consternation a bit funny, and I started smiling with my answers, which must of signalled that we were honest and benign, and not vagabondish brigands deceptively claiming to be pilgrims.

We stayed with the Franciscans for two days and nights. At our request, they gave us work to do, cleaning and organizing a decrepit library. They were a new community in an old monastery, which was also a kind of Shrine called Campocavallo. We joined them in their little cloister for prayer and meals, and soon a robust Christian friendship grew between us. Some of the friars were from the Philippines, and grateful for the chance to speak English. We had to keep moving, however, and departed the community with professions of mutual prayers and best wishes.

The next evening we were close to Loreto. In the dim light of dusk, the basilica became visible on its mount, though still a number of miles away. We prayed the rosary and shared some milk and biscuits someone gave us as we tramped along the highway. When we entered the town of Loreto, it had become dark. The religious communities that ran the hotels with all their “amenities” could not allow two penniless pilgrims to sleep for free. A nun admitted their hotel was a four-star hotel. That night we did what failed mendicants like us did: we slept in a park on benches. I tied a plastic bag around my feet and another one with breathing holes around my head for protection from the bugs and breeze. Depleted, and a bit dejected at the inglorious finale to our journey, I experienced a deep feeling of impoverishment. At journey’s end, there had been no room in the inn. What would happen now?

When morning came, the birds began to chirp and the roosters in the valleys began to crow, I got up from the bench, and hiked up to the shrine of Our Lady of Loreto.

I walked into the basilica, and up to the marble-enclosed holy house. On the inside, you could see the ancient stones of Mary's home. I saw words inscribed in Latin: "Hic verbum caro factum est" (Here, the Word because flesh). Being within the space where Gabriel had appeared to Mary struck me profoundly. I sat down and prayed. I remembered that Mary had been empty and poor. Even after her marriage to Joseph, they were homeless for a time. They had to flee to a foreign land. My own week of temporary poverty was nothing compared to theirs. And theirs was nothing compared to God’s, who had emptied himself and became man.

Yet Mary, by this self-emptying, had set in motion the reversal of the curse of sin, by listening to the word of God and following it, the "new Eve". Her poverty was linked to her trusting dependence on a provident God.

On our last day in Loreto, I was spiritually full but, I must admit, hungry (again), and really needed to sleep on a bed. We knocked on one door to ask for help, and a priest answered it. I told him our story that we were pilgrims to Loreto but had no money for a place to sleep. I’ll never forget that priest. He dug his hands into his pocket and gave me some of his own money for food. Then he said come with me, and we jumped into his car and he brought us to his parish hall, gave me a key and showed us a place where we could sleep. That night, sleep never felt so good.

At the shrine in Loreto there was a list of saints who had visited there, going back hundreds of years. It included favourites like St. Therese of Lisieux and St. Maximillian Kolbe. There was also a gallery of art exclusively of scenes of the Annunciation. But I will mainly remember the Shrine to Our Lady of Loreto as the place where I learned to trust in God.

“For the almighty has done great things for me, and holy is his name.”

- J.O.

Two years later I was a Jesuit novice. In the novitiates of the Society of Jesus novices make an "Ignatian pilgrimage" for one month's duration. My week-long pilgrimage in Italy had so prepared me by hard consolation, that the longer one in Canada was, by God’s mercy, smooth and blessed. St. Ignatius praised pilgrimages as practices that conduce to God powerfully, and the increase of our faith, hope and love.

My travelling companion on the pilgrimage to Loreto is now a Benedictine monk at an abbey in England.

In 2019 Pope Francis added Our Lady of Loreto to the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church. It is celebrated on December 10.

Comments

Post a Comment