Life and Death in Jamaica

A few years ago, I found myself confined behind the brick walls of the Jesuit house in Kingston, Jamaica, while gunfire raged outside. For three days, army, police and gunmen were battling for control of the city, the catalyst being a government decision to arrest Jamaica’s leading criminal don. Drought had made the city even more combustible, and the urban water shortage was making life difficult. Ironically, those three days were the first time in months I had opportunity to reflect – a rest from the days of teaching at the inner-city school. I spent those house-bound mornings reading and thinking about why I had been led to this violent but hospitable and beautiful island nation.

Above all, I was there because I had been sent, like my fellow novices from Canada, who at the same time were serving in Haiti and the native missions of northern Ontario. We were meant to meet Christ in the face of the poor. Now, as the city was being rocked by the trauma of violence, I was anxious to get out and help in some way.

On the fourth day, I got a call from a priest at our inner-city parish St. Annie’s beside the school, about a mile away in Denham Town. The gunfire had mostly subsided, and I was to try to come and help bring food for the local residents. Sister Beverly, a Franciscan sister who could go almost anywhere, picked me up in a white van. We drove around Kingston, loading sacks of dry foods, and praying we would be able to get to our church, which was behind army checkpoints. At an entry street soldiers stopped the van and questioned us; they didn't want more guns smuggled into the zone. I realized nervously that I had no identification on me that day. But they must have thought that the only white person silly enough to be there would be a missionary-type, so they let us through, and we reached St. Annie's with our cargo.

|

| St. Annie's RC Church, West Kingston |

A restless crowd gathered quickly, hungry after four days of fighting, martial law and curfew, and then a band of soldiers arrived. An angry major told us we needed permission to distribute food since the situation was still volatile. We called his superior, and soon the major was ordering his soldiers to help us for the rest of the day! I stepped around the ends of machine guns, carrying family-sized bags of rice and beans to the crowd, which was now lining up thanks to the presence of the soldiers. We learned the church was the only source of food. Humanitarian groups were not being allowed inside the zone, although we did see one car arrive and begin handing out food, but it got mobbed and fled the scene.

The next day, Sr. Beverly began worrying about the people in occupied Tivoli Gardens, the fugitive's own neighbourhood and epicentre of the conflict not far from the church. It had been tightly sealed off from the public for almost a week, except for a one-hour “guided tour” for the media by the army. It was still in a state of high-tension as soldiers conducted house-to-house searches looking for arms and their fugitive. I wasn’t sure what they would think of us showing up, but I was willing to give it a try. A married couple, the Edwards, were parishioners of ours had managed to walk out of Tivoli that morning to look for food. They were eager to get back to their family, so perhaps we could drive them. Mr. Edwards, an usher in the church, had had his back grazed by bullets when soldiers fired into his apartment window during the initial assault, but aside from some trauma, was mostly okay. They heard soldiers yell “there’s a gunman!” just before getting themselves and their children onto the floor. Their six-year-old son David jumped down just before bullets struck the wall where he had been sitting.

|

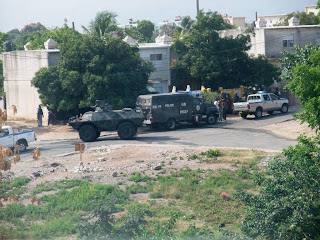

| Security patrol as viewed from the rectory during the events of May 2010 |

I got in the van with Sr. Beverly, the Edwards, and sacks of food. As we drove towards Tivoli, we could see that soldiers everywhere were tired; they had been on the streets for five days now, never sure whether or not a sharpshooter would fire at them. I heard residents yell, “sistah!” as we drove past, and I could tell she was tempted, but every stop would mean a small crowd and antsy soldiers.

Somehow, we just rolled into Tivoli. The presence of security forces was about ten times that of the parish area. We glided past dozens of eagle-eyed soldiers and police in flak-jackets, and nobody stopped us. The place was like a war zone. Rubble from barricades and the fallout from the explosives was everywhere. It was evident that this had been a fairly well-kept community by West Kingston standards thanks to its ample drug money, but now it looked like war-torn Beirut. There were no children anywhere – just some women and elderly people wandering the streets looking dazed. The news had reported that around 500 men had been taken away to the national arena for processing.

Once inside their small apartment, the Edwards showed me the spray of machine-gun holes on the wall above their bed. It was a sobering sight. Then Mr. Edwards took me up to higher floors to visit other residents of their building. He told me soldiers had taken a young man and shot him dead in his own living room. He was not even a gunman the mother said, as she pointed out the spot. Another woman showed me the bedroom where her son had been shot. The sheets on the bed were still blood-stained. Many were in shock, or perhaps stoic resignation. Sister Beverly asked me to pray with them, which I did, holding back emotion as we asked God for justice, peace, and forgiveness in the midst of all this human misery.

Once inside their small apartment, the Edwards showed me the spray of machine-gun holes on the wall above their bed. It was a sobering sight. Then Mr. Edwards took me up to higher floors to visit other residents of their building. He told me soldiers had taken a young man and shot him dead in his own living room. He was not even a gunman the mother said, as she pointed out the spot. Another woman showed me the bedroom where her son had been shot. The sheets on the bed were still blood-stained. Many were in shock, or perhaps stoic resignation. Sister Beverly asked me to pray with them, which I did, holding back emotion as we asked God for justice, peace, and forgiveness in the midst of all this human misery.

It was not easy to see God’s presence in midst of this chaos, nor to sort out the justice from the injustice, the right from the wrong. Some say that violence would always be present in paradise, that the poisonous insects come with the mangos. Later, at our evening Mass back at the Jesuit centre, I struggled to concentrate with the adrenaline and swirl of the day’s imagery. Yet the gestures and words of the priest called me back to the sacrifice that illumines all human suffering. The drama of the day was somehow contained in the larger drama of the cross, and I had a strong sense that all human pain could be found within the body broken of him whose life was poured out for all. The bread offered at that altar was that of Jesus 2000 years ago and of Jesus that day in West Kingston. Then I could see a little more my purpose there. God had asked me to come and participate a little in the cross of this corner of the world, to be “buried” for a time there, and be a witness of God’s love for his people, even as they were witnessing the same to me.

During those days of conflict, the rain began to pour again. The water was both a blessing for the parched city, and perhaps a damper on the flames of violence. Soon I would be preparing to take vows back home in Canada, confirming a vocation that had begun in the waters of my baptism years ago. But I knew that in Jamaica, through an experience of the paschal mystery, and in the beautiful faces of his people, I had encountered Christ once more. Just as he had died, so also he would rise again.

|

| Jamaica's hope: the effervescent spirit of St. Annie's School grade fours |

Wow, John! I had no idea you experienced this. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteJohn, that's an amazing story. You told it to me in person when you were home, but it's good to read it again. I hope that you are well!

ReplyDelete